A guest post from my colleague Andrea Berger:

Chinpo Shipping (Private) Pty is our model proliferation finance prosecution. Or at least it was, until last week, when it all came apart at the seams.

In June 2014, Singaporean prosecutors filed charges against Chinpo Shipping and its director for its involvement in facilitating the shipment of the largest consignment of North Korean weapons ever seized. A year earlier, the Chong Chon Gang was stopped in the Panama Canal on its way from Cuba to North Korea. Panamanian authorities searched the vessel and found 25 containers of military equipment concealed beneath over 200,000 bags of sugar. The loot included two MiG fighter jets and additional engines, military vehicles, and surface-to-air missile systems, amongst other things. More about the cargo here, and in paragraphs 84-89 of the 2014 UN Panel of Experts report.

Further investigations revealed that it was a Singaporean company, Chinpo Shipping Ltd, that paid $72,000 for the vessel’s passage through the Panama Canal. Chinpo’s Director, Tan Cheng Hoe had been providing services related to North Korean maritime trade since the 1970s. His primary client was North Korea’s Ocean Maritime Management, which orchestrated the Chong Chon Gang shipment, and which was sanctioned by the UN for contributing to proliferation shortly thereafter.

Singaporean prosecutors filed two charges against Tan and Chinpo: one for carrying on a remittance business without a valid remittance license; and one for providing financial services or transferring financial assets or resources “that may reasonably be used to contribute to the nuclear-related, ballistic missile-related, or other weapons of mass destruction-related programs or activities of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea” (Regulation 12b of Singapore’s United Nations Regulations 2010).

That was a big deal. Proliferation finance prosecutions, where the leading offense is about the flow of funds rather than the flow of goods per se, are extremely rare. Several facilitators of Iranian nuclear- or missile-related goods procurement were previously prosecuted in the US, partly on the basis of financial transactions connected to the deals. But in those cases the charges were mostly filed pursuant to anti-money laundering legislation, which carries the potential for bigger collective fines, and where guilt is often easier to prove. Chinpo was different, and many hoped it would show other countries that proliferation finance prosecutions were doable.

The judge in the district court that first heard the case found Chinpo guilty on both counts. The first charge, relating to unlicensed remittances, was always going to be pie from a prosecution standpoint. Tan had agreed to let OMM use his bank accounts with United Overseas Bank, International Commercial Bank, and Bank of China to facilitate OMM’s international business. At OMM’s behest, between April 2009 and July 2013 Tan performed over 600 wire transfers worth $40 million. Oh, and to make it shadier, a North Korean would periodically rock up to the bank and withdraw about half a million in mint US dollar notes from Tan’s accounts. Chinpo did not have a remittance license when it did any of this. So when it appealed the initial conviction on this charge, the Singaporean High Court judge quickly upheld the District Judge’s verdict.

The second count is where it all gets tricky. Singapore’s Regulation 12(b) focuses purely on the provision of financial services that aid North Korea’s WMD or missile activities. In order for Tan to be convicted under 12(b), the prosecution needed to prove that the financial transfer could have reasonably contributed to North Korea’s WMD programs. The prosecution opted to make that link by bringing in a witness, Dr Graham Ong-Webb, to testify that the shipment of conventional weapons aboard the Chong Chon Gang clearly supported Pyongyang’s WMD and missile programs, because the kit could be used to defend North Korean nuclear and missile sites. Yes, in the DPRK there are certainly SAMs proximate to priority sites, including nuclear ones. But does that mean SAMs could reasonably contribute to the nuke program? Discuss.

As I said at the time in an article for 38 North:

Ultimately, prosecutors were lucky. The judge determined, based on the testimony of a single expert witness, that the surface-to-air systems found on board the Chong Chon Gang could be used to defend North Korean “nuclear missile sites.” That’s thin ice.

The Singaporean High Court on 12 May 2017 agreed with Chinpo’s appeal on the same issue (the judgment is available here). “If we accept this opinion as conclusive of ‘what could reasonably be used to contribute’ to the [nuclear program] of the DPRK…then even mundane logistics such as food and toiletries that facilitated the functioning of the [nuclear program] of the DPRK” could also contribute. I’m not sure where Yongbyon gets its shampoo, but I take their point.

The court added that there is a “large logical leap between transferring funds for the passage of a vessel through the Panama Canal (without knowing the presence of the Material on the vessel) and contributing that the transfer could contribute to the [nuclear program] of the DPRK”. Their conclusion: unless it’s going directly to the nuclear program, it’s not proliferation finance. The appeals court even implied that funding the transport of an assembled nuclear warhead (don’t get me started) might be too indirect for regulation 12(b).

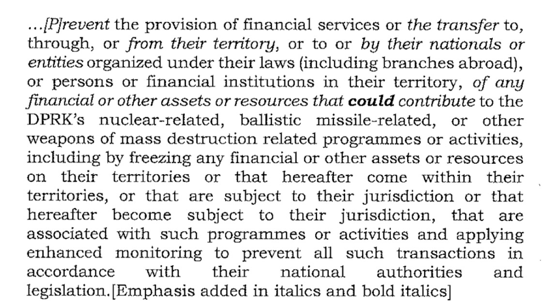

To be fair, prosecutors should not have had to perform such legal gymnastics in the first place. The language in 12b of the Singaporean statute is pulled from Paragraph 18 of UNSCR 1874 (2009):

But in just lifting language from paragraph 18, the statute misses out the financial obligations captured in other parts of the resolution, namely in paragraphs 9 and 10, which ban financial transactions related to conventional weapons. Had Singapore drafted and updated its national regulations with sufficient specificity, or made reference to other activities that proliferators are prohibited from engaging in pursuant to relevant UN resolutions, this would never have been an issue.

Sure, prosecutors could have tried to charge Chinpo under the part of the Singaporean statute that covers provision of services related to conventional weapons (Regulation 5, read with 13), but to do so they would have had to prove that Tan and Chinpo staff knew that illicit weapons were on board the Chong Chon Gang. Hard to do. That same burden didn’t exist in relation to regulation 12b, which is why it was chosen.

That sort of backfired on prosecutors too, because the Court of Appeal ended up getting spelling out its own (completely self-contradicting) conclusions that Chinpo staff might have had to know about the weapons in the Chon Chong Gang to be convicted under 12(b). Dear Singapore: if your statute requires the prosecution to prove that a defendant knew the whole illegal masterplan, it will be worthless for enforcement. North Korea is way too good at evasion for us to be able to do that, even in the most straightforward cases.

Debacles like this are perfect examples of the need for greater attention to the global deficiencies in implementing UN Security Council Resolutions on the DPRK. No, the issue isn’t sexy, and DPRK sanctions nerds like me sound like broken records when we keep bringing it up. But if Singapore is actually comparatively advanced in implementation, think about how far behind we are elsewhere, and the practical problems those gaps might create for stopping perpetrators of the next Chong Chon Gang. We have so far to go just to get the arms-focused sanctions we passed in 2006 and 2009 right. Don’t even get me started on the truck load of stuff the Security Council dumped on everyone in 2016.

In short, for those of us working to help build capacity globally on counter-proliferation finance, and particularly to create a basket of success stories in passing and enforcing CPF legislation, this outcome really sets us back.

Here is the correct link for the UN Panel of Experts 2014 report:

http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2014/147

Was leaving out the sections related to conventional weapons done on purpose, or was it just an oversight in updating the regulations? It would be interesting to know if they only wanted the lesser burden of proof to apply to WMD issues.

Also, if I’m recalling correctly the kid in Manhattan Project replaced the plutonium with shampoo, so it -might- be important. What a movie.

My understanding was that 12(b) is in effect a copy-paste job from 2094 para 18, and as a consequence misses how other restrictions within UN resolutions interact with it. Not deliberate, just not a diligent drafting job.