Readers may recall my earlier rantings about a company called ‘Glocom’, a North Korean military communications firm masquerading as Malaysian, and selling missile navigation systems and other arms-related products around the world. The company was outed by the UN Panel of Experts and a Reuters special investigation in February, around the time of Kim Jong Nam’s assassination. We did a podcast on the company, which has juicy details of the case and the “perfect storm” that Malaysia faced as a result. But five months on, it looks like Glocom is still at it.

In the aftermath of the February revelations, Kuala Lumpur pledged to investigate Glocom and its networks. Corporate registry documents now indicate that most – but not all – of the firms controlled by the North Koreans behind Glocom are in the process of being struck off the registry. Malaysian authorities appear to have been busy, though it is unclear why some of the North Korean-linked entities in the network have been left untouched, at least on paper.

You might think that a Malaysian police investigation, a UN investigation, and all that negative media attention to Glocom and its products would make the network go underground for a while. Its brand has been significantly and publicly tainted, and its links to North Korea demonstrated beyond any doubt. Future customers would have difficulty feigning ignorance of the company’s ties, or going through with a deal without at some point stumbling across evidence that Glocom is a front for North Korean intelligence, unless they do no due diligence whatsoever. Not even a Google search. So it is logical that North Korea would seek to create a new, shadowy brand for its military communications exports…..right?

Apparently, Glocom is not our traditional game of counter-proliferation ‘whack-a-mole’. Between 15-27 July 2017, the company published a set of new marketing videos on Youtube.

North Korea’s decision to stick with the tarred Glocom brand could indicate a number of things: that Pyongyang has become reliant on that particular branding for its success in selling military communications technology overseas; or, perhaps, that its customers are the type that simply don’t care.

The fact that these videos made their way onto YouTube and have yet to be removed is also interesting. Service providers have an obligation to ensure that they are not contributing to violations of sanctions and export controls, as outlined in the laws of the countries they operate in. Alibaba, for example, came under fire for this a few years ago.

I’m no expert in the legal specifics of circumstances like this, but YouTube appears to be aware that it has such an obligation, including as it relates to North Korea sanctions. Compliance considerations are likely partly behind YouTube’s recent removal of other North Korea-linked content, namely North Korean official media or promotional videos. Recent rounds of US sanctions have targeted the North Korean entities which produce propaganda, so redistributing and earning advertising revenue from their content may be seen as either as a sanctions breach or coming close enough for the US Office of Foreign Assets Control to eventually interpret it as such.

However, the fact that Glocom was able to put up new videos without being immediately flagged, suggests YouTube’s North Korea-focused compliance efforts are list-based or otherwise driven by individual cases of reported content. Even though its activities are firmly illegal, Glocom itself has not been sanctioned or listed as the alias of another designated entity, and so will not appear on the formal sanctions lists against which private sector entities usually screen. This is a recurring issue in the sanctions space – the portion of sanctions violations that even the most well-meaning companies independently catch drops substantially if the individual/entity’s name does not appear on a formal list.

I digress. In addition to the new Glocom website that was launched in January 2017 just before the UN report and Reuters stories were published, these five videos are a real treat. The contrast between the quality of some of them, and the North Korean military product brochures from a few years ago that I used to study, is striking.

That may be in part to do with the fact that an external graphics specialist helped Glocom make some of the snazzy new videos, which look like they are straight out of Call of Duty. I defer to the brilliant members of our Slack channel to tell me if they actually borrow from Call of Duty. It wouldn’t be the first time.

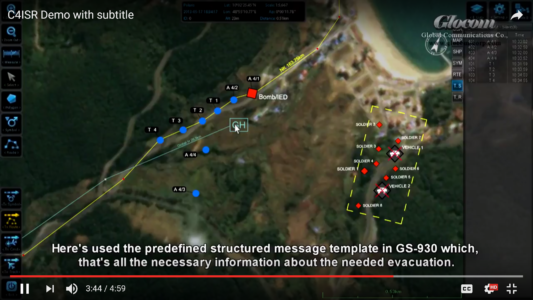

Glocom’s C4ISR video is by far my favourite. The Korean-accented narrator introduces the watcher to “Operation Prometheus”, in which Glocom-equipped forces deliver supplies to formerly terrorist-controlled areas. This scenario should give you an idea of the kind of customer North Korea has in mind for Glocom products. I also loved the Prometheus reference – giving fire to all mankind. Nice touch.

The video producers try to throw off anyone trying to geolocate Operation Prometheus, by showing fake coordinates that land you in the middle of nowhere in the Somalian desert (coordinates are at the very top center of the screenshot below). Needless to say, the lushly forested setting of Prometheus looks much more like North Korea than the Somalian desert.

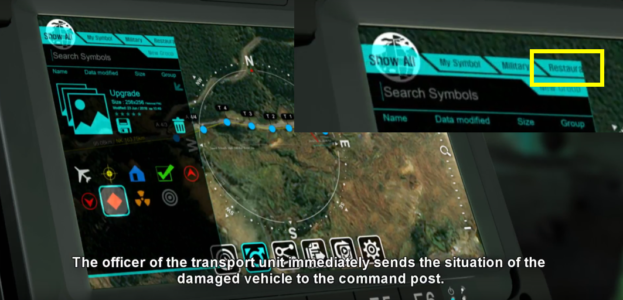

My eagle-eyed colleague Dave Schmerler pointed out a few other fun things. For example, the control screens bear remarkable resemblance to those used for North Korea’s solid fuel missile tests, right down to the power button and colour scheme.

Glocom also appears to have been concerned about whether users would get peckish whilst on duty.

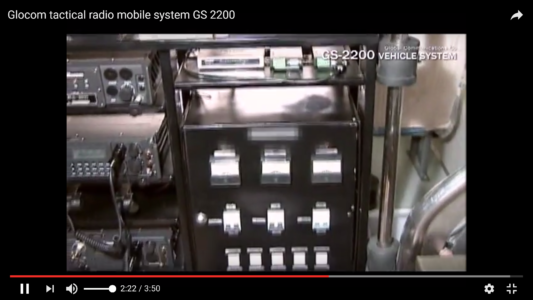

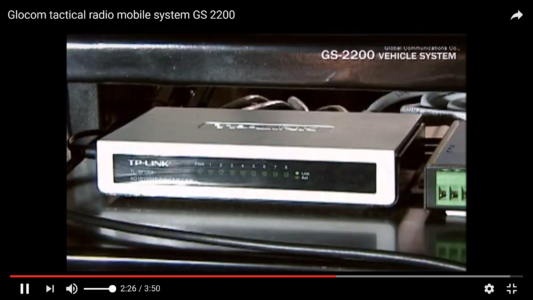

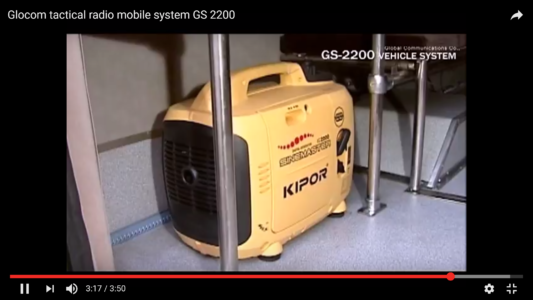

Nuggets from other videos which sparked my interest include efforts to blur some of the brand labels on Glocom products and components, while leaving others visible. Take a look at the GS-2200 Vehicle System video to see what I mean (screenshots are included here for when the videos inevitably get taken down).

Following the various investigations earlier in 2017, some of Glocom’s suppliers may have noticed their goods ending up in places they preferred them not to be. Glocom’s brochures, for example, if carefully studied, revealed some well-known logos on sub-components. It is possible that these suppliers investigated and shut down the channels through which their products were illicitly procured, prompting greater North Korean sensitivity towards the images they release.

Nevertheless, the videos show that some components in the GS-2200 vehicle command and control system are from UK manufacturers, though they are fairly commercially available and are likely to have been sourced from China.

Also noteworthy are the systems Glocom advertises for unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) applications. Analyses of the North Korean UAVs that crashed in 2015 showed that the platforms used externally-sourced navigation, communications, and imaging technology. Some attempts by North Korea to source such goods from Western countries have also been thwarted by relevant authorities and reported, again shining a light on parts of the North Korean supply chain. If North Korea is now marketing this technology, does that indicate that North Korea has found a steady foreign sub-components supply chain for the UAV systems that it exports? Or that it is able to make those goods indigenously?

Further reader observations from the Glocom videos or website are always gratefully received. I’ll shortly be publishing a detailed case study report on the Glocom network and its structure, evasive tactics, and financial conduits, so keep your eyes peeled for that too.

Lastly, if you haven’t already, find an hour to watch the BBC Documentary “North Korea: A Murder in the Family“. The show’s producers not only put together an excellent account of the Kim Jong Nam murder, but in the process found the new Glocom YouTube channel. That’s top sleuthing.

aaaaaaannnnnnddd it*s gone.

That account has been blocked or removed by YT.