The Tomahawk Land Attack Missile, or TLAM, is named after the Tomahawk — a Native American axe. If you have ever seen a Western movie, the tomahawk is thrown overhand, and can be quite dangerous as Ed Ames — who played a Native Amerian on the television program Daniel Boone — demonstrated on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson:

As this little moment with Johnny suggests, when it comes to Tomahawks, aim is important!

I recently drafted a little memo on the Nuclear Tomahawk, the TLAM-N, and the problem of clobbering — when a Tomahawk missile goes astray. The short version is that Japanese officials should let the US retire the TLAM-N in 2013 because the possibility that it might crash in Japan or South Korea en route to targets in North Korea makes it all but unusable.

As this story in Kyodo News by Masakatsu Ota would suggest, the Japanese public would flip if they understood how TLAM-N works.

Below is an html version with hyperlinks. You can also download a pdf version with citations that looks more like an “academic” paper. It is still very much a draft; comments are welcome.

A Problem with the Nuclear Tomahawk

Jeffrey Lewis

December 14, 2009

As part of his September 1991 “Presidential Nuclear Initiatives,” President George H. W. Bush ordered the Navy to “withdraw all tactical nuclear weapons from its surface ships and attack submarines.” This included all nuclear-armed Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles (TLAM-N) deployed on US ships, including some Los Angeles-class attack submarines. Nuclear Tomahawk has been in storage since the Navy completed the withdrawal in early 1992. The Navy now wants to complete retirement of the system by 2013.

Some current and former US and Japanese government officials oppose retirement of the Nuclear Tomahawk. A Secretary of Defense Task Force criticized the Navy for assessing the weapon on grounds of whether it is “militarily cost-effective.” The Task Force argued that this criterion “ignores the weapon’s political value.” In other contexts, US and Japanese officials have argued that the credibility of the US nuclear umbrella “relies heavily on the deployment” of the TLAM-N.

This memo, using only unclassified information, explains in plain language why the Department of Defense should retire the Nuclear Tomahawk. One shortcoming of the Nuclear Tomahawk stands out: the possibility that a Nuclear Tomahawk would accidentally crash in an allied country like Japan or South Korea.

The problem is that the mid-1980s Tomahawk guidance system directs the missile to its target by comparing digital maps stored in an onboard computer against radar measurements of the terrain below the missile. The Nuclear Tomahawk, for example, needs to complete seven of nine “position-fixes” – matching a map to actual terrain — to arm the nuclear weapon. Each “fix” requires a map of rough and unique terrain approximately 7-8 kilometers in length. Since distinctive terrain is unusual by definition, the need for at least nine distinctive 8 km-long maps routinely results in routes of 100 km or more. Since terrain data must be extremely accurate, the Navy tends to prefer routes over friendly countries which allow the United States the access needed to make accurate maps in advance.

During the course of its flight along this “ingress route” a Tomahawk missile can drift off course and fly into the terrain that is supposed to guide it – an event known as “clobbering.” During the initial phase of Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003, approximately ten conventionally-armed Tomahawk missiles went astray, crashing in Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Iran. In response to the political fallout from these stray missiles, the Navy suspended launches of Tomahawk missiles from ships in the Mediterranean and Red Seas. These Tomahawks were newer and had more modern guidance systems than the nuclear versions kept in storage since 1992.

(Vice Admiral Timothy Keating stated that “less than ten” out of 800 Tomahawk missiles (about 1.25 percent) “have been found in Turkey and in Saudi Arabia.” Other reports suggest the number of Tomahawks fired was 675, which would bring the total closer to 1.5 percent.)

Navy officials are rightly concerned about the political consequences if a US nuclear weapon were to fall in a friendly country like Turkey, Saudi Arabia, South Korea or Japan. The 1966 crash of a US B-52 bomber carrying four nuclear weapons near Palomares, Spain – which strained relations with US allies and eventually resulted in changes to US Air Force operational practices – remains a potent memory.

This problem is especially vexing in scenarios involving North Korea. Although North Korea is rugged and mountainous, it is also relatively small and surrounded by featureless water. For obvious reasons, the United States is unlikely to fly nuclear-armed Tomahawk cruise missiles over Russia or China. As a result, the most plausible ingress routes lie over South Korea and, to some extent, Japan.

It is very surprising that officials within the Japanese government have lobbied the United States to retain the Nuclear Tomahawk. If the Japanese and South Korean public understood how Nuclear Tomahawk works and that a failure might result in a nuclear weapon crash landing on their territory, the result would be a public relations nightmare. It is important to note that the Nuclear Tomahawk’s 150 kiloton W80 nuclear weapon would not detonate if it fell in South Korea or Japan while flying over either country. However, within Japan, even the possibility of Tomahawk overflights and crashes would raise sensitive issues related to the transit of nuclear weapons through Japanese territory and waters. Within South Korea, similar concerns would be complicated by the colonial overtones of Japanese officials pressing for Nuclear Tomahawk overflights of South Korea. The mere possibility of public disclosure alone ought to impel retirement of the Nuclear Tomahawk.

The Tomahawk Missile

The Tomahawk Land Attack Missile (TLAM) is a cruise missile that can be launched from US Navy ships and submarines. The missile was initially deployed in the 1980s. The original nuclear variant has a range of 2500 km.

The United States today has four types of Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles in its arsenal – three conventional and one nuclear. For convenience, this paper refers to the nuclear-variant as Nuclear Tomahawk. It is properly called TLAM-N – for Tomahawk Land Attack Missile – Nuclear. The other variants – the TLAM-C, D and E are referred to collectively as Conventional Tomahawk. (TLAM-E is sometimes called Tactical Tomahawk or TacTom.)

Figure 1: Tomahawk Cruise Missiles in US Inventory

| Block | Designation | IOC | Guidance | Warhead |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block II | TLAM-N | 1986 | INS, TERCOM | W80 nuclear warhead |

| Block III | TLAM-C | 1994 | INS, TERCOM, DSMAC, GPS | 1,000 lb unitary warhead |

| TLAM-D | 1994 | Sub-muntions dispenser | ||

| Block IV | TLAM-E | 2004 | INS, TERCOM, DSMAC, GPS | 1,000 lb unitary warhead |

Source: Raytheon.

As part of his September 1991 “Presidential Nuclear Initiatives,” President George H. W. Bush ordered the Navy to “withdraw all tactical nuclear weapons from its surface ships and attack submarines.” This included all Nuclear Tomahawks deployed on USN ships, including some Los Angeles-class attack submarines. All Nuclear Tomahawks have been in storage since the Navy completed the withdrawal in early 1992.

Over the same period, the United States has developed two successive generations of Tomahawk missiles (the Block III and Block IV) with improved guidance. One feature has been the integration of satellite guidance using the Global Positioning System. (The United States does not use GPS for nuclear weapons guidance due to concerns regarding jamming and spoofing.) Although some Block II Conventional Tomahawks remained in the inventory though the 1990s, U.S. regional combatant commanders strongly prefer the newer Block III version. In March 1999, Navy officials testified that about 90 percent of TLAMs used in recent military operations had been the Block III weapon.

Today, all remaining Block II Conventional Tomahawks have been converted to the Block III version. The Navy wants to complete retirement of the remaining Block II Nuclear Tomahawk systems by 2013

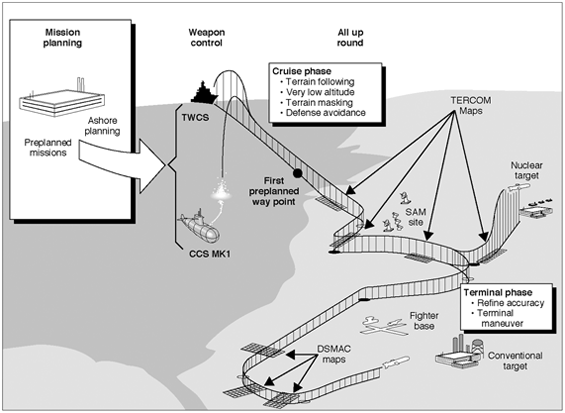

Figure 2: Block II Tomahawk Flight Profile

Source: GAO/NSIAD-95-116, Cruise Missiles: Proven Capability Should Affect Aircraft and Force Structure Requirements, General Accounting Office, April 1995, p.15.

Tomahawk Guidance

Nuclear Tomahawk uses a 1980s-era system called Terrain Contour Matching (TERCOM) to guide the missile over the majority of its flight. Launched from the sea, the TLAM flies a preprogrammed route to landfall and then starts matching the observed terrain, using radar, to maps stored in its onboard computers. The Nuclear Tomahawk, for example, needs to complete seven of nine “position-fixes” – matching a map to actual terrain – to arm the nuclear weapon.

Each “fix” requires a map of rough and distinctive terrain approximately 7-8 km in length. (Each map comprises approximately 64 samples of 122 meters-long strips of terrain.) Since distinctive terrain is by definition unusual, a collection of nine or more maps 8 km in length routinely results in routes that are hundreds of kilometers in length. Since terrain data must be extremely accurate, the Navy tends to prefer routes over friendly countries that allow the United States enough access to make very accurate maps in advance.

Despite claims of outstanding Tomahawk performance during the Operation Desert Storm, a subsequent analysis by the Center for Naval Analyses and the Defense Intelligence Agency raised questions about the effectiveness of the system. Although the analysis remains classified, a General Accountability Office report concluded, based on the CNA/DIA analysis, that Tomahawk “accuracy was less than has been implied.” Among the problems that GAO pointed to included “the relatively flat, featureless desert terrain in theater made it difficult for the Defense Mapping Agency to produce usable TERCOM ingress routes…”

The flat, featureless terrain between the Persian Gulf and Baghdad forced the United States to create “ingress” routes for Tomahawk missiles for Operation Desert Storm in 1991 that took the missiles over Iran Saudi Arabia, Syria and Turkey:

Yet other complications persisted. The gray steel boxes housing the missiles topside contained secrets to which few men were privy. One secret – which would remain classified even after the war – was the route the Tomahawks would fly to Baghdad. The missile’s navigation over land was determined by terrain-contour matching, a technique by which readings from a radar altimeter were continuously compared with land elevations on a digitized map drawn from satellite images and stored in the missile’s computer. Broken country — mountains, valleys, bluffs — was required for the missile to read its position and avoid “clobbering,” plowing into the ground.

For shooters from the Red Sea, the high desert of western Iraq was sufficiently rugged. But for Wisconsin and other ships firing from the Persian Gulf, most of southeastern Iraq and Kuwait was hopelessly flat. After weeks of study, only one suitable route was found for Tomahawks from the gulf: up the rugged mountains of western Iran, followed by a left turn across the border and into the Iraqi capital. Navy missile planners in Hawaii and Virginia mapped the routes and programmed the weapons. They also seeded the missiles’ software with a “friendly virus” that scrambled much of the sensitive computer coding during flight in case a clobbered Tomahawk fell into unfriendly hands. A third set of Tomahawks, carried aboard ships in the Mediterranean, were assigned routes across the mountains of Turkey and eastern Syria.

Not until a few days before the war was to begin, however, had the White House and National Security Council suddenly realized that war plans called for dozens and perhaps hundreds of missiles to fly over Turkey, Syria, and Iran, the last a nation chronically hostile to the United States. President Bush’s advisers had been flabbergasted. (“Look,” Powell declared during one White House meeting, “I’ve been showing you the flight lines for weeks. We didn’t have them going over white paper!”) After contemplating the alternative-scrubbing the Tomahawks and attacking their well-guarded targets with piloted aircraft — Bush assented to the Iranian overflight. Tehran would not be told of the intrusion. But on Sunday night, January 13, Bush prohibited Tomahawk launches from the eastern Mediterranean; neither the Turks nor the Syrians had agreed to American overflights, and the president considered Turkey in particular too vital an ally to risk offending.

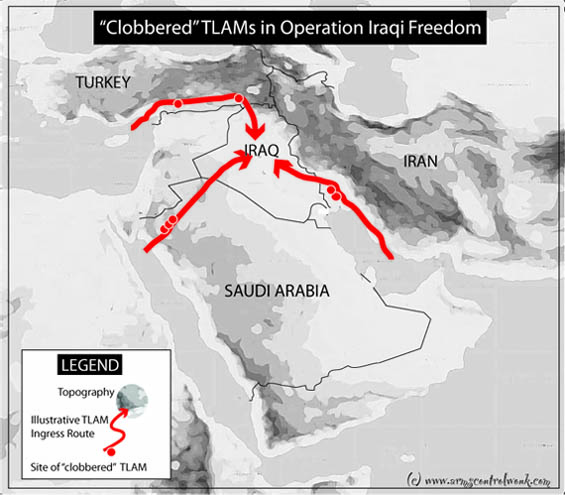

The United States used the same “ingress routes” for conventional Tomahawk strikes in 2003, during the initial phase of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Between 1-2 percent of all Conventional Tomahawks were “clobbered” en route to their target in one of three countries: Iran, Saudi Arabia or Turkey. Additional missiles may have been lost over Iraq. The map below shows the ingress route and the location, based on press accounts, of six “clobbered” Tomahawks. It is worth noting that these crashes occurred involved newer Block III models of the Tomahawk missile that supplemented onboard TERCOM systems with satellite-aided Global Positioning System (GPS) guidance. The existing Block II Nuclear Tomahawks, which do not have GPS, would likely experience worse rates of clobbering. (Moreover, because GPS signals are subject to jamming and spoofing, the United States military has been reluctant to use satellite-guidance for nuclear weapons.)

Figure 3: Clobbered Tomahawk Missiles in Operation Iraqi Freedom

The crashes in Turkey and Saudi Arabia created difficult a political problem for the United States. According to one press account, locals pelted US vehicles with stones as US soldiers attempted to recover the clobbered Tomahawks in Turkey. The two images below show a clobbered Tomahawk, guarded by Turkish security forces and some onlookers who have gathered at the crash site. As a result of complaints from Ankara and Riyadh, the United States suspended Tomahawk launches from the Mediterranean and Red Seas in late March 2003.

Figure 4: A Clobbered Tomahawk Missile In Turkey

Credit: Mehdi Fedouach/AFP/Getty Images. March 29, 2003, Buyukmerdes, Turkey.

Figure 5: A Crowd Gathers Near the Clobbered Tomahawk

Credit: Mehdi Fedouach/AFP/Getty Images. March 29, 2003, Buyukmerdes, Turkey.

Issues for Japan and South Korea

Some officials have suggested that TLAM-N is the only unique, tactical nuclear weapon system that demonstrates the commitment of the United States to the security of Japan and South Korea. As a result, some Japanese Government Officials in Tokyo and Washington have pressed the Office of the Secretary of Defense to overturn the Navy’s decision to retire Nuclear Tomahawk.

North Korea has rugged terrain that is suitable for TERCOM mapping. According to the Central Intelligence Agency, North Korea’s terrain comprises “mostly hills and mountains separated by deep, narrow valleys.” However, North Korea is also small and surrounded largely by featureless ocean. At its narrowest point, North Korea is less than 200 km wide.

Although there may be some potential ingress routes involving the long finger of North Korea that extends to the northeast along the Sea of Japan, the need for highly accurate maps, proximity to the Chinese and Russian borders, and the preference for multiple axes of attack probably means that mission planners must consider some ingress routes that fly over non-North Korean territory.

For obvious reasons, the United States is unlikely to fly Nuclear Tomahawk over China or Russia. This leaves South Korea and, possibly Japan, as possible sources of terrain for TERCOM matches. It is important to note that the Nuclear Tomahawk’s 150 kiloton W80 nuclear weapon would not detonate if it fell in South Korea or Japan while flying over either country. As mentioned above, the Nuclear Tomahawk will not arm the warhead unless the onboard guidance computer successfully complete seven of nine contour matches – a condition precluded if the missile “clobbers” early in flight before the seventh match.

Even without a nuclear explosion, the political ramifications of crashing a nuclear-armed missile into a friendly country would be profound. A similar event happened in 1968 when a B-52 carrying nuclear weapons collided with an in flight refueling tanker over Palomares, Spain, dropping nuclear weapons into fields and the Mediterranean Sea. The incident created tensions between the United States and its allies, notably Spain, and – in combination with a subsequent accident at Thule, Greenland – led to the elimination of “Chrome Dome” flights with nuclear weapons.

Simple disclosure of this problem in the Japanese or South Korean press could create a political firestorm. The lobbying of one or more Japanese government agencies to maintain a nuclear missile whose mission would depend upon being able to fly over Japan and South Korea, which involves the risk of crashing in those countries, could lead to a severe political crisis, if the Japanese and South Korean publics became aware of these facts. In Japan, the issue of nuclear weapons transiting Japanese territory and waters is extraordinarily sensitive. Nuclear Tomahawk directly raises the issue of nuclear weapons transit, albeit in wartime, at a time when Japanese newspapers are publishing details of previous “secret” agreements between Tokyo and Washington regarding US nuclear weapons in Japan. In South Korea, where memories of Japan’s occupation have left a lingering sense of distrust, the revelation that Japanese bureaucrats are lobbying to retain a nuclear weapons system that would fly over South Korean homes and farms would deepen tensions between two important U.S. allies.

The mere possibility of public disclosure, therefore, ought to impel retirement of the Nuclear Tomahawk.

Why not a program to replace their guidance kits with modernized, GPS-enabled navigation?

Would the program be more expensive than manufacturing or developing weapons to augment strategic/tactical need?

JDAM kits are cheap…why can’t a similar solution be found for the aging TLAMs?

Nice work, Jeffrey, but I’d still be more worried about the consequences of a TLAM-N detonating in North Korea than crashing relatively harmlessly in South Korea or Japan.

J House:

A perfectly reasonable question.

1. The Tomahawk Block IIIs that crashed in OIF had GPS. It may reduce the problem, but evidently does not eliminate it below 1 percent. Of course, you go to (nuclear) war with the (TLAMs) you have. The ones we have are not GPS aided (and, in fact, do not even use DSMAC). So one has to replace them, which brings us back to the Navy’s conclusion that they are not “militarily cost-effective.”

2. A GPS module is subject to jamming and spoofing, which raises its own set of issues. Violating the “black box” rule on a nuclear weapon system would be a big organizational change for the United States military.

Not that I think the “black box” is sacrosanct, just that I observe the Navy might prefer non-GPS solutions for nuclear munitions.

Jeffrey, great article (I love the Carson clip!), and I think you’ve done the right thing publishing it, but aren’t your protestations about what would happen “if” these facts were publicly disclosed in Japan and/or Korea a little disingenuous? I mean, in publishing this article aren’t you expecting (or at least hoping for) the debate to reach audiences in those countries?

Jeffrey,

Interesting and informative analysis, but I have to wonder if there would ever be a real-world situation where we’d use TLAM-N’s against North Korea instead of some other nuclear weapon.

Additionally, Palomares isn’t a good analogy since that occurred during peacetime and you’re talking about a war. If there’s a nuclear shooting war going on I think worries about the political fallout from a crashed Tomahawk wouldn’t be a huge concern in the minds of policymakers.

I think you identified the real purpose for these weapons in your second paragraph – they are political tools. If that is their real purpose (and I think it is) then the weapon employment issues you raise are interesting but ultimately irrelevant. If it comes down to nuclear war with North Korea there are much better employment options than dragging old missiles out of storage and loading them on ships and/or subs which probably don’t even train for a nuclear mission anymore.

On minor quibble on mapping:

I don’t think that is the case at all, especially today. “Friendly” territory does not provide any mapping advantages that I can see.

Jeffrey,

is there a reason to suspect that it is necessarily the guidance systems that is leading to the clobberings? I realize it is not said so explicitly (and I am no expert on this…), but it does appear that you implicate the guidance systems somehow.

Could it not be other subsystems that are failing?

In any case, I do agree with you that it is smart to retire these as nuclear delivery platforms due to the shortfall issue.

While we are at it, we should also retire all other nuclear platforms besides sub-based ICBMs, of which probably ~40 will suffice for deterrent purposes.

The Palomares accident was in 1966. The Thule accident was indeed later, in 1968.

T Nishi:

Thanks for that. I am terrible with dates. I’ve changed the paper and the post to reflect the correct date for Palomares.

Jeffrey

Andy:

As usual, you found the weakest spot in the whole analysis. I’ve spent countless hours trying to track down how TERCOM maps are made — which is not something our friends at NGIA are very talkative about. (This is why I was musing about the difference between imagery-based and imagery-derived products a few weeks ago.) You may be right that remote sensing has improved so much that on-site surveys are no longer necessary.

Early on, however, it appears that overflight and ground-surveys were used to create the DTED database from which NGIA makes TERCOM maps. (To say nothing of the maps themselves.) Here is one of then-NIMA’s cryptic references on the subject:

The most detailed discussion I’ve seen about making TERCOM maps is in Earth Data and New Weapons by Jay L. Larson

but Larson is deliberately vague about exactly how DMA made TERCOM maps.

In at least one study from the early 1990s, DTED was not very accurate compared with field measurements, which would suggest a preference for friendly overflight when possible. Whether this is still the case today, I just don’t know. In any event, I suspect North Korea is small enough (and wooded enough) that overflying South Korea, and possible Japan, is required.

Further comments on this are welcome.

Jeffrey,

Have you seen this RAND paper by Larson? It contains some details on how TERCOM maps are generated (see especially footnote 72 on page 21.)

I don’t know much about TERCOM specifically, but I’m familiar with DTED, which is the data that TERCOM is built from. DTED accuracy improved considerably with the Shuttle radar mapping mission in 2000. Combined with high-resolution satellite imagery, a high degree of precision and accuracy can be achieved over denied areas. So I think the digital data feeding TERCOM maps has only gotten better over the years.

One detail I can’t pin down is TERCOM’s minimum resolution requirement. I’m guessing it’s probably DTED level 1 (~90 meters). If that’s the case, the map accuracy should not be an issue since we have high-quality DTED level 2 (~30 meters) of most of the planet.

I disagree that flying over Japan or (much more likely) South Korea is required – North Korea isn’t so small that it would be difficult to get nine matches. Operationally, however, military planners would want to minimize flight-time over hostile terrain, particularly since North Korea has probably the densest low-altitude AAA coverage on earth. Tomahawks are one of the more vulnerable delivery options in a place like Korea, which is another reason it’s not likely they would be used in any conflict on the peninsula.

Changing the shape of the terrain is not as difficult as it sounds. If an attack is detected chaff rockets fired from hilltops can alter the radar return enough to confuse the guidance computer. This is especially true if the attack is coming from a predictable direction.

Moreover, the ocean presents a relatively “clean” environment for detecting incoming missiles. Being able to approach from a land frontier allows the missile to use the terrain for cover.

No, they’re not cost-effective and it would take a whole regiment of Hollywood scriptwriters to think of circumstances under which a nuclear warhead is desperately needed but a Trident missile cannot be used.

Just ran across this Rand appendix from 1982 which contains a lot of dated, but interesting and probably relevant, information on TERCOM.

Did China or America mind this problem much in the 1980s, when USS New Jersey, cruisers, and submarines patrolled in the E China Sea and the Yellow Sea with Tomahawk Block I/II against targets in the USSR (and maybe Mongolia)?

Andy:

Thanks. I hadn’t seen the second Larson paper.

Jeffrey,

It is not clear what the difference would be between launching and detonating a 150kt TLAM-N W80 warhead and a 100kt Trident D5 W76 warhead other than the explosive effects of the 50% yield difference. The distinction between a ‘tactical’ and a ‘strategic’ system in this context seems irrelevant. The accuracy of the D5 is now said to be measured in ‘metres’, accurate enough for a nuclear attack and comparable to the TLAM-N.

DOD arguments that TLAM-N somehow offers a unique contribution to the US extended deterrence guarantee to Japan in the context of a nuclear-armed DPRK makes no sense if Trident D5 in various configurations (the UK reportedly deploys a ‘sub-strategic’ variant of its Anglicised W76 Trident warhead that delivers a 10kt yield) can deliver the same effect.

If, as one might suspect, the deliverable effect of the TLAM-N in a DPRK war scenario is NOT the driving motivation for maintaining the TLAM-N capability, and USN is NOT keen to retain it for operational and budgetary reasons, then the rationales for retaining TLAM-N are entirely political. In which case the motivations driving the political meanings being assigned to TLAM-N as an essential component of Japan’s strategic security blanket need to be explored further.

How does routing TLAM-N near Russian or Chinese borders differ from firing intercontinental range nuclear ballistic missiles to targets similar distance from said borders? If the US is not keen on doing the former, why would it consider the latter any less troublesome option? How precisely can russian/chinese early warning systems predict the warheads trajectory and be sure they won’t be falling on their territory? Is it faster than the time they have to conclude are they being attacked or not, before they have to launch or risk losing their weapons to counter-force attacks?

A lot of amateur questions, I know, but I feel they must be answered before Trident can be considered for replacement for TLAM-N. Especially since other replacement options exists as well, say, short(er) range stand-off missiles launched from aircraft.

The link to the PDF version isn’t working. Could you check it? Interested in the details and footnotes. Thanks!

The weak spot in this analysis is that the only scenario in which a nuclear tomahawk is flying is one in which a NK or PRC launch of a nuke either has already occurred or is imminent, in which case the citizens of SK and Japan are already out of their minds with terror.

Jeff, the next question is, do you think the navy should have a nuclear tipped cruise missile at all?

The LRASM program, which aims to produce an anti ship missile that can operate without GPS guidance, could be conceivably adjusted to carry a nuclear warhead. In that case, you would have the nuclear weapon capability, with a modern package in a modern airframe, giving the navy its tactical deterrence capability.

As other comments have stated, were the US to use a nuclear weapon on the Korean peninsula, it would be cruise missile or bomb based, as ICBMs are too unsettling to Russia and China.

Perhaps, the navy also wants to keep the TLAM-N because it wants some say at the shrinking, but still relevant, non intercontinental nuclear weapons table.

And, perhaps Japan is correct in recognizing that only cruise missile nuclear weapons would be used against North Korea. So, Japan may know that they are less than perfect, that their use risks nuclear waste being strewn across their countryside, but they are willing to take the risk, because they want the US to maintain a solid capability to nuke North Korea.

Another phenomenon due to the TLAM guidance method that might be commented on.

Since (as the article testifies) there are often limited regions of suitable unique terrain this has the effect of creating “missile highways”: areas where all of the missiles in a region will be flying the same path for part of their mission.

This element of predictability may not be as serious a weakness for TLAM-N since the number of missions being flown is not very high, one hopes.

The differences between a 150kt W80 and a 100kt W76 are,

1. The W-80 isn’t necessarily a 150 kiloton weapon; it can allegedly be dialed down to 5 kilotons. The W-76 seems to be 100 kilotons or nothing.

2. The W-80 is delivered with a CEP of roughly 10 meters; the W-76 100 meters or so. That makes a difference if you’re trying to destroy an underground target with a 5-kt bomb, and most of the DPRK’s interesting targets are underground.

3. The W-76 rides atop a big flaming arrow that says to every satellite in the sky, “strategic nuclear weapon here, heading in the general direction of Moscow and/or Beijing”. The W-80’s delivery system, in this context, is much less likely to be seen as an existential threat by any great power. Or seen at all, until it is retroactively obvious where it was aimed.

So, yes, a TLAM-N is a somewhat more credible threat in a limited regional conflict than a Trident. Same “positive” effect at less cost and risk, so more likely to be used if it is available.

But the same can be said, and more, about the B-61, and that definitely is available. If there’s still an application for the TLAM-N, it would be in e.g. Iran, which might be a target for limited nuclear attack but might plausibly obtain air defenses that would make direct attack by manned bombers problematic. I don’t see anyone selling S-300s or the like to North Korea, and I don’t know what the Japanese are thinking that they don’t consider the B-2/B-61 combo a sufficient nuclear umbrella.

I am scratching my head because I was under the impression that the US converted several (four) Ohio class submarines to be able to fire cruise missiles instead of ICBMs. This modification, as far as I know, was carried out this decade.

If I am correct (will gladly be corrected), I fail to understande the underlying argument of the paper according to which the US Navy wants to do away with nuclear tipped cruise missiles.

SEK:

The SSGNs carry conventional cruise missiles.

The clarity of your writing is remarkable.

I recently read the interview of yours with the Carnegie Endowment. In the interview you briefly mention that one of the benefits of eliminating some of the US nuclear arsenal is that it frees up time for dual trained forces to focus on their conventional missions. Do you think that would be another advantage of eliminating the TLAM/N? According to Dennis C. Blair in Integration and Separation of Nuclear and Non-nuclear Planning and Forces the nuclear mission has a separate personnel and administrative system.

Cassie:

I have never given such an interview. Maybe you mean James Acton?

Jeffrey

I am speaking of this interview:

http://www.carnegieendowment.org/files/0929_transcript_nuclear_posture1.pdf

this section:

“And I will digress with one example of that. I was recently in South Korea, and I kept talking

about reducing the number of nuclear weapons. And one reason, by the way, to do that, is you

might free up, say, B-52s, some of which are currently training for nuclear missions, to go off and actually be useful, like, you know, dropping bombs on Taliban.”

I was not very specific in my reference. My question is- do you think that eliminating TLAM/N would free up time for submarines in the same way that taking away the bombs out of Europe could free up time for attacking the taliban for the B-52 bombers.

Right. I just didn’t remember making that comment.

I think the Navy would like to have to stop training crews on TLAM-N. It would be a modest increase in flexibility. How much, I can’t say since I don’t know how many days each year those crews on certain SSNs spend training for TLAM-N.

More time would be saved on the mission planning and logistics end for stratcom than training on SSN’s, which is probably at most a few hours per quarter. It is not realistic that W-76’s could be generated in time to defend the US in a crisis, and B-2 is a recently proven and highly proficient precision delivery platform. I think they are going to stick around as they are feasible as a flexible and survivable weapon in the post-SIOP battle.