Apologies for the nonexistent blogging as of late — I wrote a book! (More on that later.) Writing takes an enormous amount of time, which is to say pretty much every second that doesn’t involve chasing two tiny lunatics around the house. I also got sucked into a huge number of massive projects, none of which I have any funding for — Saudi Arabia, Myanmar, you name it. So, I’ve been busy.

But I am back. And I hope to start churning out new blog posts based on the past six months of intellectual “investment.” Here we go with the first one — the Hagap (하갑) Underground Facility in North Korea.

1.

Hagap Underground Facility

One of the big questions is where North Korea’s other centrifuge facilities might be located. I can’t answer that for sure, but I’ve spent a lot of time squinting at a large underground facility near Hagap, located at: 40° 04′ 48″ N, 126° 10′ 56″ E.

This facility is noted in Wikimapia, but there is quite a bit about it in open-source materials that deserves to be collected all in one place. This is that place. The site isn’t always mentioned by name, but it comes up again and again.

As best I can tell, the underground facility near Hagap was a matched pair with the better-known UGF near Kumchangni (Kumchang-ri). The United States detected construction at both around the same time. As best I can tell, the United States intelligence community concluded the UGFs at Hagap and Kumchangni were both nuclear-related because the same engineering unit that built both had also worked on Yongbyon. (Although the gas-graphite reactor and reprocessing line at Yongbyon are aboveground, there are lesser-known tunnels that raised Swedish eyebrows once upon a time.) Other details, I would argue, were then fitted around that general connection. (Mike Chinoy describes some of the ancillary details in an excerpt from Meltdown.)

The earliest mention I can find of Hagap in the press is in January 1998 — several months before Kumchangni. Someone leaked a DIA report to Eric Rosenberg of the Hearst Washington Bureau asserting (on the basis of very little evidence as far as I can tell) that although the “function of this site [at Hagap] has not been determined, but it could be intended as a nuclear production and/or storage site.”

Behind closed doors, the leak played out as a sort of prologue to the Kumchangni fiasco. It seems someone also leaked the report to Congressional Republicans, who sand-bagged Madeleine Albright in a July 1998 closed hearing. New York Times reporter James Risen later described the scene:

Witness this incident, not previously disclosed: Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright had just completed an upbeat, top-secret briefing for the House leadership in July 1998 on the Clinton administration’s dealings with North Korea when one lawmaker posed the question he had been waiting to ask:

What was Dr. Albright’s assessment of a recent intelligence report suggesting that North Korea had built a storage installation that housed components for nuclear warheads? And how long had she known about the report?

Dr. Albright, according to several people who were present, replied that she had learned of the evidence just two weeks earlier. In a startling departure from the united front that top administration officials usually present to Congress, Lt. Gen. Patrick Hughes, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, immediately contradicted the secretary of state.

“Madame Secretary, I have to correct the record,” said General Hughes, whose agency had produced the report, according to others who were there. “You were briefed on that intelligence a year ago.”

Hagap stayed quiet, possibly because a nuclear-weapons storage site wouldn’t violate the 1994 Agreed Framework in quite the same way as an underground reactor or reprocessing facility. So, about a month later, in August 1998, the New York Times had a front-page story about the other underground facility, the one near Kumchangni: NORTH KOREA SITE AN A-BOMB PLANT, U.S. AGENCIES SAY. This triggered an intense period of diplomacy, ultimately resulting in a US visit to the facility. Turns out, it could not hold a reactor and was really not well-suited for a reprocessing facility, either. (The layout was just too weird. More on that in a bit.)

After Kumchangni, there wasn’t much interest in trying again, particularly with a facility that probably didn’t violate the terms of the agreement.

2.

Enrichment

Then, in 2002, the United States intelligence community figured out that the North Koreans were buying LOTS of aluminum tubes — enough for thousands of centrifuges. Combined with other evidence from the Khan network, the United States intelligence community began to suspect that North Korea’s centrifuge program was moving past basic R&D. This is an important distinction — both the Clinton and Bush Administrations thought the North Koreans were cheating with gas centrifuges to enrich uranium; what changed in 2002 was the assessed scale of the cheating. (I summarized this in a post a few years ago.)

Suddenly, Hagap was very interesting again. Press reports claimed the United States intelligence community was interested in three sites: a complex with tunnels near Yeongjeo-ri”(영조리) located at 41°21’48.67″N, 127° 3’58.12″E, the Academy of Sciences in Pyongyang, and — always listed first — our friend, the large underground facility near Hagap. (A defector report that places centrifuge operations near Huichon may refer to Hagap — Huichon is less than 20 km up river.)

Joby Warrick wrote a story that hinted Hagap was the main site, but he couldn’t get anyone to confirm that on the record. Another reporter tried a different approach with then-Deputy SecState Richard Armitage:

MR. ARMITAGE: It is our view, and what we’ve spoken publicly about is Yongbyon, which has a possibility of reprocessing the 8,000 rods of spent fuel — and we don’t quite know the exact status of Yongbyon — and another highly enriched uranium facility.

Q You think there is another one?

MR. ARMITAGE: And that’s what we have talked to the North Koreans about.

Q Right. Is it the Hagap facility?

MR. ARMITAGE: I don’t even remember the name. I don’t know.

Q And you — you said —

MR. ARMITAGE: If I knew it I wouldn’t tell you, but I —

Nice try. On the other hand, a “defense official” told Inside Defense that “U.S. intelligence analysts do not believe the Hagap complex is part of North Korea’s uranium enrichment effort” adding that “U.S. surveillance efforts have detected ‘articles of an historical or archival nature’ being moved into the underground facility.” For awhile, some people fingered Hagap as a site for high-explosives testing — although focus for that activity eventually moved to a place called Yongdoktong (sometimes Youngdoktong). I don’t know whether testing moved, or just our focus. One sometimes see references to Hagap as a nuclear test site, which I think is a corrupted reference to testing of conventional high explosives for an implosion design.

In the end, the facility remained a mystery — as Barbara Demick wrote:

The facility in Chagang, known as Hagap, has been known to U.S. intelligence since 1996 and suspected of being variously a reprocessing facility, a high-explosives test site or even an underground nuclear reactor. But Daniel Pinkston, a North Korea military analyst for the Center for Nonproliferation Studies in Monterey, Calif., says more recent information suggests that it is merely a vast underground archive for the ruling Korean Workers’ Party.

Ultimately, the US intelligence community decided that maybe there was no centrifuge facility after all — until the collapse of the Six Party Process in April 2009. The North Koreans built a new gas centrifuge plant at Yongbyon so fast — they showed it to Sig Hecker in November 2010 — that most of us assume this wasn’t their first.

3.

Revisiting Hagap

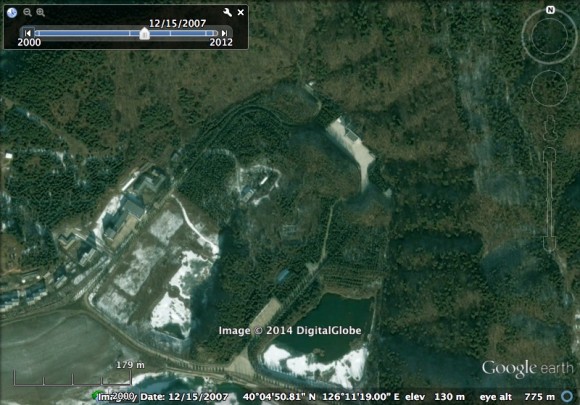

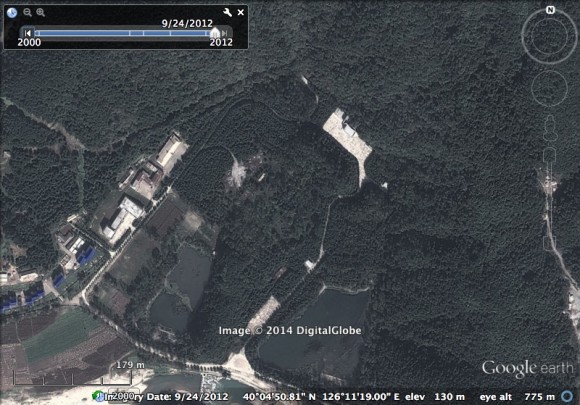

It is worth revisiting the construction timeline of Hagap. Honestly, the completion of the facility looks pretty consistent with large procurements in the 2001-2002 time period. Here are shots from 2000, 2007, 2009 and 2012:

Moreover, the facility underwent a second expansion after 2009 — just as Yongbyon ramped up. There are a number of buildings that appear nestled in the valleys just to the east of the facility. Here are shots from 2009 and 2012:

It’s impossible to know if this is the centrifuge facility, or just a giant warehouse for statues of various Kim family members, but its easy to see why it is so interesting.

One possible explanation is that tunnels make us crazy — every time we think North Korea is up to something (which is basically always), we imagine that something is happening deep underground near Hagap. It’s become the Area 51 of North Korean underground facilities, a canvas for every conspiracy theory that comes along. There are a bunch weirdos who think aliens attended Kim Jong Il’s funeral.(I’ll just link to the debunking.) I am sort of bummed they didn’t have Kang stay over at Hagap.

The other possibility, though, is that it really is something — but we just don’t know what that is because the debates about Kumchangni and the uranium enrichment program are really proxies for a broader debate about our North Korea policy that doesn’t permit too much pondering of the evidence, interesting though it is. I can’t tell you that Hagap houses another enrichment facility. But just ruminating on the debate seems suggest some interesting things about our own domestic political debates.

4.

Kumchangni Revisited

So, let me close with a really unusual idea. What if North Korea originally intended Kumchangni to house centrifuges?

When the US teams visited Kumchangni, it became clear the site was not going to be a reactor and probably not a reprocessing plant. Here are the findings from the US team that visited:

— The site at Kumchang-ni does not contain a plutonium production reactor or reprocessing plant, either completed or under construction.

— Given the current size and configuration of the underground area, the site is unsuitable for the installation of a plutonium production reactor, especially a graphite-moderated reactor of the type North Korea has built at Yongbyon.

— The site is also not well designed for a reprocessing plant. Nevertheless, since the site is a large underground area, it could support such a facility in the future with substantial modifications.

— At this point in time the U.S. cannot rule out the possibility that the site was intended for other nuclear-related uses although it does not appear to be currently configured to support any large industrial nuclear functions.

The issue was the layout of the facility, which was weird. Here is one account of the series of narrow tunnels in a grid:

The 14-member U.S. inspection team that was ultimately allowed to visit in late May was forced to walk past a line of barking German shepherds before entering the site. Intimidation? But then they were free to walk through the six miles of empty tunnels, taking photos and videos. The tunnels were in a grid pattern: four running north to south and 17 running east to west. The east-west chambers were about 40 feet wide and about 20 feet high. The walls were unfinished and there was no equipment.

Was the site an elaborate decoy? Not likely, said one U.S. official. It took thousands of North Koreans about a decade to build it. An underground shelter? Also unlikely; there were no signs of amenities. Could it be adapted for nuclear energy material reprocessing? It would need drainage; otherwise radioactive material would spread throughout the facility.

“We don’t know what it’s supposed to be,” said one U.S. official.

You have to use your imagination, but what they are saying is that the complex consisted of 17 halls, each 12 meters wide and a little less than 500 meters long. Let’s assume the facility is a square — then it looks something like this with about 100,000 square meters of floorspace (17 tunnels that are each about 12 x 500).

So let me just wonder aloud — or in print, I guess — does that look like it might have been for centrifuges? The footprint is much larger than, say, either underground enrichment hall at Natanz (which are 190 x 170 m each, and constructed in a cut-and-cover fashion). The last finding — “cannot rule out the possibility that the site was intended for other nuclear-related uses although it does not appear to be currently configured to support any large industrial nuclear functions” — is pretty wishy-washy. A lot depends on what “currently configured” means, I guess. Whatever Kumchangni was supposed to be, we never found out.

The DPRK, by the way, didn’t exactly deny that the facility was nuclear — or promise that it never would be. KCNA quoted the spokesman for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs stating that “The visit proved objectively that the underground facility in Kumchang-ri is an empty tunnel, not related to nuclear development at all. As a result, it was clearly proved once again that we have been sincerely implementing the Geneva agreed framework. The point is for what the tunnel in Kumchang-ri will be used. This depends entirely upon the attitude of the U.S. side concerning the implementation of the DPRK-U.S. agreement reached in New York.”

That statement looks rather different, in hindsight.

I don’t mean to suggest that I am persuaded that Kumchangni was for a centrifuge program, any more than I am convinced Hagap was built for that purpose. But I do think that the history of these two facilities is interesting and worth setting down in one place, largely because I suspect we haven’t heard the last of them.

There is another interesting UGF near Hamhung at: 39°55’04.40″ N 127°38’50.78″ E

“Was the site an elaborate decoy? Not likely, said one U.S. official. It took thousands of North Koreans about a decade to build it.”

It’s still possible that North Korea purposefully baited the U.S. with intelligence leads beforehand, and it wouldn’t be the only time. Recall that North Korea later tried to trick the U.S. into boarding a freighter back in 2009 right after the U.S. publicly redeclared its right under UN resolutions to search suspect North Korean freighters on the high seas. The U.S. didn’t take the bait that time, and just shadowed the ship instead as it plodded to its destination.

http://www.gizmodo.co.uk/2014/02/training-for-underground-warfare-at-a-nuclear-weapons-complex/

Today, West Fort Hood still plays a similar role in the Army. It’s used to train special units in underground combat; a dark and difficult way to fight, simulating what combat might be like inside, say, the caves of Afghanistan. The troops have upgraded from simple night vision goggles to using robots for help with reconnaissance.

—No one would *admit it* if the U.S. government is training soldiers to fight it out in North Korea, right?

—But then, would not proof that the U.S. is not planning this come from South Korean? Are the South Koreans training soldiers to fight for control of Hagap?

Ahem. That’s not a very good likeness of Kang Sok Ju.

Thanks for doing this review, Jeffrey! It’s very educational. And welcome back to blogging.

But who is the North Korean Kodos?

It’s Barack Obama. Obviously.

I hope that new book will be good as the “Chinese nuke” book what I purchased couple years ago.

Hopefully there is going to be a paperback version or are you going all electronic this time?

It’s a real book. I expect there will be a paperback version, as well as an electronic one.

http://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/1452011/chinese-scientists-urged-develop-new-thorium-nuclear-reactors-2024

The deadline to develop a new design of nuclear power plant has been brought forward by 15 years as the central government tries to reduce the nation’s reliance on smog-producing coal-fired power stations.

A team of scientists in Shanghai had originally been given 25 years to try to develop the world’s first nuclear plant using the radioactive element thorium as fuel rather than uranium, but they have now been told they have 10, the researchers said.

“In the past the government was interested in nuclear power because of the energy shortage. Now they are more interested because of smog,” said Professor Li Zhong, a scientist working on the project.

Cooks saved nuke missile crews from test failure

BY ROBERT BURNS (AP NATIONAL SECURITY WRITER)Published: March 18, 2014

WASHINGTON – Failings last spring by nuclear missile operators at an Air Force base in North Dakota were worse than first reported, according to documents obtained by The Associated Press.

Airmen responsible for missile operations at Minot Air Force Base would have failed their portion of a major inspection in March 2013 but managed a “marginal” rating because their poor marks were blended with the better performance of support staff – like cooks and facilities managers – and they got a boost from the base’s highly rated training program. The “marginal” rating, the equivalent of a “D” in school, was reported previously. Now, details of the low performance by the launch officers, or missileers, entrusted with the keys to missiles have been revealed.

“Missileer technical proficiency substandard,” one Air Force briefing slide says. “Remainder (of missile operations team) raised grade to marginal.

http://progress-index.com/news/2.397/cooks-saved-nuke-missile-crews-from-test-failure-1.1651272

I think I’ve understood it… Well, not all, but part of it.

This conception is similar to the Russian Typhoon-class multi-pressure hull. In this concept, two parallel pressure hulls connected to each other provide the main living space, so that even the destruction of one of them wouldn’t mean the loss of the ship.

In this case, the North Koreans built 17 tunnels to provide the space they needed, and 4 communication tunnels to connect them with each other. In fact, this conception is optimized against airstrikes : not only would a successful hit in one of the tunnels leave most of the facility undamaged, but even making such a hit would be difficult, because most shots would tend to end in the rock between the tunnels.

This implies several things.

First, this means that the North Koreans believed there was a risk of airstrikes against whatever they intended to put there. However, they certainly know the US well enough to know that it doesn’t even remotely cares about blowing up their (or anybody’s) historical artifacts. Thus, I believe the “archive” interpretation is certainly a clever misdirection.

Second, the North Koreans were willing to accept that part of this facility could be damaged or destroyed by such attacks. This, in turns, implies several things :

– It cannot have been intended as a nuclear reprocessing centre. A successful hit in such a facility would contaminate it disastrously, thus negating all the survivability of the concept.

– For the same reason, it cannot have been intended as a weapons storage site, since a successful hit would have blown it all. For such a use, buiding fully separate tunnels would have made more sense;

– And, whatever it was they wanted to do here, it was something that could be continued after the destruction of a part of the facility. Thus, the size of the construction reflects only the scale of the intended operation, not its complexity (that is, it couldn’t be a tank factory, for example, because a hit somewhere in the production line would have brought the whole factory to a halt – it was something that could be done inside a single portion of the tunnel, and that they intended to duplicate in all of them).

However, since no mention is made of its depth, or of any pressure reinforcements, I guess we can assume it wasn’t built to withstand direct nuclear strikes. This means its protection was likely not meant for wartime, only for classical airstrikes. Thus, an underground shelter is also unlikely :

– In case of a nuclear war, putting high-value people here would only help the US to locate and kill them;

– In case of a non-nuclear conflict, these people would be better protected by simply leaving them in the general population.

In conclusion, Jeffrey, I have to say that your hypothesis of a centrifuge program has at the very least some credibility. In fact, I find it far more convincing than the underground archive idea.

If it is possible, I am both marveling at how elegant this idea is, while also worrying that it leans on a slender reed. Like most elegant ideas, I suppose. I cant think of a better explanation, that’s for sure.

While our policymakers proclaim their phobia about nuclear energy, they seem to have no such inhibitions whatsoever about nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed ships, submarines and aircraft entering the country, and nuclear weapons possibly being implanted in it, despite the constitutional prohibition on nuclear weapons in the Philippines. This is obvious in the way B. S. III seems to be approaching the subject of enhanced military cooperation with the United States.

http://manilastandardtoday.com/2014/03/21/can-aquino-answer-this-/

Mysterious underground facility with multiple parallel tunnels; does NK happen to have a historian fan-boy of Speer & Von Braun and this represents their version of http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mittelwerk? Lots of digging, check, unfinished / unrefined, check – does it have the local camp for the slave-labor and other signature attributes of the worst examples of inhumanity?

Jeffery: Good to have you back.. Can you explain why NK aluminum tubes are for centrifuge applications while Iraqi aluminum tubes are not? Particularly thick-walled centrifugally ground tubes? (From your comment in Section 2 on enrichment)

The DPRK claimed their tubes, too, were for an artillery system before melting them down. The tubes were Russian. (There was an interdicted shipment of German tubes that never made it to the DPRK, as well.) The DPRK allowed the US to test the smelted aluminum. The US found traces of uranium: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/12/20/AR2007122002196.html

(With apologies to Jules Winnfield, “You know inspectors tend to notice shit like you’re spinning tubes drenched in fucking uranium.”)

Unlike Iraq, the DPRK has a centrifuge program and says the current generation of centrifuges use maraging steel (well, an “iron alloy” which sound a lot like maraging steel.) Given the dimensions of the Russian and German tubes (20 cm by 110 cm) most people I know think the aluminum tubes were for outer casings rather than rotors.

Of course, as I’ve written previously, I think the tendency of the Kim Jong Il to pose with machined tubes of various sizes might be one of the greatest act of proliferation-trolling I’ve ever seen: http://38north.org/2013/09/jlewis090413/

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2584235/Weather-experts-baffled-mystery-plume-New-Mexico-radar-near-1945-nuclear-bomb-test-site.html

PreviousNext

Weather experts baffled by mystery plume on New Mexico radar near 1945 nuclear bomb test site

There is speculation that the cloud could be the result of a weapons test

But the U.S. has not done A-bomb tests since the Test Ban Treaty in 1992

Plume originated from White Sands Missile Range in Socorro count

Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2584235/Weather-experts-baffled-mystery-plume-New-Mexico-radar-near-1945-nuclear-bomb-test-site.html#ixzz2wetrOWTv

Follow us: @MailOnline on Twitter | DailyMail on Facebook