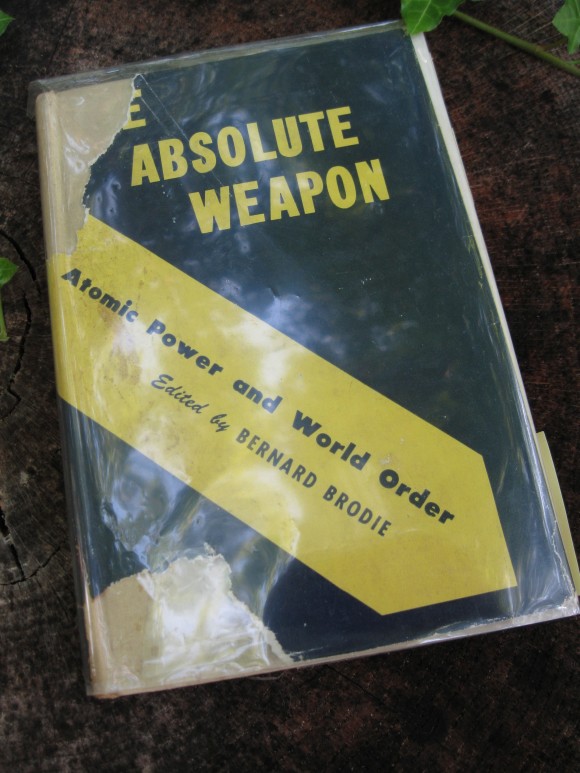

Aspiring Wonks: The Absolute Weapon (1946) is required reading. It’s a slim book of essays written by an exceptional group of analysts based at the Yale Institute of International Studies. In these pages, you will find the most prescient, earliest forecast of the implications of atomic power for world order (the book’s subtitle), as well as the origins of the strategy of deterrence.

The best essays and the best quotes come from the book’s editor, Bernard Brodie. Brodie was interested in naval history and in reaching a broader audience, having written two books —Sea Power in the Machine Age (1941) and A Layman’s Guide to Naval Strategy (1942) — before the Bomb’s sudden appearance. Naval history turned out to be a fine prism through which to reflect upon the meaning of atomic weapons.

Here’s a sampling of Brodie’s writing:

How can we enlarge our opportunities? Can we transmute what appears to be an immediate crisis into a long-term problem, which presumably would permit the application of more varied and better considered correctives than the pitifully few and inadequate measures which seem available at the moment?

No adequate defense against the bomb exists, and the possibilities of its existence in the future are exceedingly remote… [long break] Neither military history nor an analysis of present trends in military technology leaves appreciable room for hope that means of completely frustrating attack by aerial missiles will be developed.

The new potentialities which the atomic bomb gives to sabotage must not be overrated… The FBI or its counterpart would become the first line of national defense, and the encroachment on civil liberties which would necessarily follow would far exceed in magnitude and pervasiveness anything which democracies have thus far tolerated in peacetime.

Everything about the atomic bomb is overshadowed by the twin facts that it exists and that its destructive power is fantastically great.

A world accustomed to thinking it horrible that wars should last four or five years is now appalled at the prospect that future wars may last only a few days.

It is a weapon for aggressors, and the elements of surprise and of terror are as intrinsic to it as are the fissionable nuclei… [long break] If the atomic bomb can be used without fear of substantial retaliation in kind, it will clearly encourage aggression.

Thus, the first and most vital step in any American security program for the age of atomic bombs is to take measures to guarantee to ourselves in case of attack the possibility of retaliation in kind.

Thus far the chief purpose of our military establishment has been to win wars. From now on its chief purpose must be to avert them.

The bomb may act as a powerful deterrent to direct aggression against great powers without preventing the political crises out of which wars generally develop.

The atomic bomb will be introduced into conflict only on a gigantic scale. No belligerent would be stupid enough, in opening itself to reprisals in kind, to use only a few bombs.

For the cheapskates/grad students amongst us — and those of us with a high tolerance for reading scanned PDFs — you can get the “Preliminary Draft” of this volume that was sent to General Eisenhower’s office in early 1946, online, courtesy of the DOE: https://www.osti.gov/opennet/detail.jsp?osti_id=16380564

It also includes some contemporary comments (I’m not sure who wrote them) in the margins (many of which are skeptical): “Can this tend to relegate the A. bomb to the position of chemical warfare in World War II?” (p. 38)

I find that comment in the draft to be fascinating. I would suggest that the writer was thinking that the mere fact that we had a significant and overwhelming amount of chemical weapons in WW2 did not mean we could actually use them, and that we still had to rely on conventional forces. This is much the same as what we have today. Very interesting stuff.

That’s how I interpret it. Which is interesting — Brodie’s articulation of deterrence seems to have caught whomever was reading it a little flat-footed. Which perhaps it ought to have: it was written in 1946, years before anyone else had the bomb (and there were many in the armed forces who believed General Groves’ assessment that the USSR would not get the bomb for 20 years, if ever).

To automatically jump to the two-body bomb problem was thinking ahead. It contrasts sharply with how the Army Air Forces were considering the problem of atomic war at the time: http://nuclearsecrecy.com/blog/2012/05/09/weekly-document-the-first-atomic-stockpile-requirements-september-1945/

I’m not sure you would want to use these comments, but here goes: Brodie, I think, like everyone else knew that governments made nuclear bombs. As a result, the doctrines he wrote about would probably exclude the wilder possibilities, for example a terrorist group demanding abolition of the death penalty world-wide.

The point is less my imaginary groups demands, than the fact that many political demands are of the sort governments do not tend to make. We’ve never had, for example, a terrorist group demand an independent Basque state, with a tacit understanding that the group would never surrender it’s nuclear weapons to the new Basque government. If an independent group was more powerful than the government, the govenment would not have a monopoly on force, and be considered a hostage, not an independent government.

Maybe the horrible point is: a government with an a-bomb has a potential weapons and bargining chip. An independent organization with an a-bomb is just a volcano wait to destroy things around it.

“…waiting to destroy the things around it.”

What a lucid and timely analysis…in 1946! Unfortunately we run in circles on some issues like and nuclear weapons and their control…This should be required reading for members of US Congress…but then, I doubt many of them can read, write or do arithmetic properly…

It is a pity Brodie did not get a Nobel prize (instead we give it away in anticipation of future accomplishments!!!)

Thank you for this book recommentation. I am very interested in books written by someone with a background in nuclear science that try to anticipate global long term developments.

For further reading i can recommend three books:

Charles Galton Darwin – The next million years

George Paget Thomson – The forseeable future

Harrison Brown – The Challenge of man´s future

All three authors have a “nuclear” background and all three books were written around the same time; Darwin worked on the Manhatten Project, Thompson was the chairman of the MAUD committee in 1940-1941 and Brown was Einsteins vice-president at the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists.

I’ve been recently going over it again at your prompting. Brodie has a truly elegant expression of deterrence:

“One must assume that, so long as bombs exist at all,the states possessing them will hold themselves in readiness at all times for instant retaliation on the fullest possible scale in the event of an atomic attack. The result would be that any potential violator of a limitation agreement would have the terrifying contemplation that not only would he lose his cities immediately on starting an attack, but that his transportation and communication systems would doubtless be gone and his industrial capacity for producing the materialsof war would be ruined. If in spite of all this he still succeeded in winning the war, he would find that he had conquered nothing but a blackened ruin. The prize for his violation of his agreement would be ashes!”

Alex:

“Elegant” is a perfectly chosen word. In my view, Brodie was a “two-fer”: Nobody writing about the Bomb was more insightful OR easier to read. Aspiring Wonks: Also check out Strategy in the Missile Age (1959). Don’t think you will be disappointed. I’ll pull some quotes from this book somewhere down the line.

MK