Big Brother and the Holding Company I could do without, but I’ve been waiting four decades for someone with Janis Joplin’s raw talent and intensity. Finally, along comes Brittany Howard of the Alabama Shakes. Patience can sometimes be rewarded.

There is now considerable impatience directed at President Obama for not doing more and working faster to achieve a world without nuclear weapons. Will it take four decades – or more – to eventually reach Global Zero? Even if he wins a second term, President Obama won’t reduce the U.S. stockpile nearly as much as President George H.W. Bush or George W. Bush. Most probably, under President Obama’s watch, as with his predecessors, more U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons will be retired because of budgetary considerations and old age than because of treaty obligations. Team Obama has taken over a year and convened countless meetings to determine how much of New START’s excess can be trimmed without harm to U.S. national security. The answer, which is likely to create great angst among his political foes and continued impatience among his backers, awaits the outcome of the election.

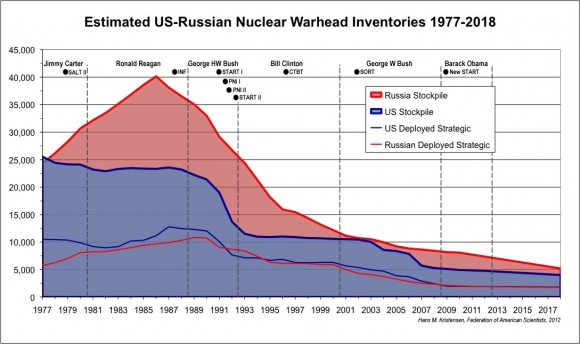

Since the 1970s, Republican presidents have had a better track record than Democrats in decisively cutting nuclear deals as well as the size of the U.S. stockpile. Hans Kristensen at the Federation of American Scientists has blogged on this topic, and has kindly prepared the accompanying graphic.

Presidents Jimmy Carter and Barack Obama vocalized their vision of a world without nuclear weapons — Carter in his inaugural address, no less — but they, like President Bill Clinton, have been cautious incrementalists on nuclear matters. President Reagan, in stark contrast, demonstrated massive disregard for nuclear orthodoxy. George H.W. Bush signed off on two strategic arms reduction treaties and wisely undertook unverifiable initiatives to reduce nonstrategic nuclear weapons, rather than try to pursue this objective by means of a treaty. Even George W. Bush, whose idea of a reasonable strategic arms reduction treaty was one that would come into effect the same day it was set to expire, oversaw a quiet, hard trim of the U.S. stockpile. The record since 1977 clearly demonstrates that both parties have worked to shrink nuclear forces and stockpiles, but Republican Presidents have had more leeway to do so than Democrats.

Now for the caveats: President Reagan was sui generis – an anti-nuclear, anti-Communist President, who was uniquely able to quiet second-guessers. President George H.W. Bush was the beneficiary of Reagan’s openings. After initial hesitation, he grabbed with both hands opportunities presented by the demise of the Soviet Union to reduce nuclear stockpiles. President George W. Bush had far more excess to trim than President Obama.

Looking ahead, deep cuts in U.S. and Russian nuclear forces will be harder to accomplish in big steps, but are very likely to continue in smaller increments over the long haul. One reason is economics. Another is the progressive weakening of key constituencies in the United States that favor larger numbers and strategic modernization programs. A third is that Russia has still not recovered from the loss of infrastructure that supported the Soviet Union’s strategic modernization programs.

[Editor adds: here’s a musical bonus.]

True, Republican presidents can be bold in arms control negotiations, while Democrats are far more cautious. That’s because the latter will be excoriated by the poltical Right for any perceived “softness” in national defense, while the former get a pass — presumably based on the 11th Commandment. As Spock said in one of the Star Trek movies, “Only a Nixon can go to China.”

Good piece Michael. I wrote my May Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists column on the history of selective GOP obstruction re: nuclear arms reduction since the end of the Cold War: http://thebulletin.org/web-edition/columnists/kingston-reif/the-politics-of-reduction.

I think even the Republicans (neocon and elsewise) will agree now that there are more deployed warheads than we need. The question is how many can we drop, can we drop delivery modes, can we agree on short, medium, longterm risks if we drop some modes and come to political consensus on those.

I think there will be consensus to arc down. I think tgere can be consensus for 1000 by 2016, say. Handing off to the next president at 999 deployed warheads would be a useful aimpoint, with continuing downwards arcs.

I would like to make the heretical suggestion that Global Zero may not be feasible or necessarily the best choice. But way lower levels – 100 is floated without being ludicrous, less might fly – are clearly good targets.

George, I take only a casual interest in strategic studies, so I would love to hear from someone more well-versed such as yourself why global zero is a bad idea.

My reasoning is that the temptation to go from zero to one or two or ten would be overwhelming for all sorts of nasty states. In a situation where the big powers only have conventional forces, a rogue nuclear state would have a free hand in regional wars. The first gulf war would have been very different if only Saddam had had WMDs.

But if USA, Russia and China each have 30, then there’s much less of an advantage. 10 warheads would easily devastate north Korea or Iran, with 20 in reserve. So the few nukes that a rogue state could quickly make would not be a credible threat against a great power like the USA.

I don’t see Global Zero happening. I do think we will see lower numbers in the future, but this will be mostly driven by budget issues. I don’t see the US giving up nuclear weapons entirely until they become obsolete.

The US military needs to participate more in reducing nuclear weapons by creating a new form of deterrence. Is it minimum deterrence? … I think it will be something else, something like a minimum deterrence that also takes into consideration counterforce targeting.

Also, where we really need to put forth the greatest effort and resources, is with stopping proliferation. In the future, it may become more feasible for more countries to produce nuclear weapons if technologies such as SILEX become affordable and effective.

Finally, what we need to work towards in arms control in future negotiations is not total elimination of warheads or delivery vehicles, but an intermediate step of shifting from less deployed delivery vehicles to more non-deployed delivery vehicles.

Two-bit dictators with a handful of nukes are only part of the problem, and not the biggest part. If it comes to that, any Great Power (and certainly the US as the last Superpower standing) can take down a classic rogue state even if we spot them a dozen A-bombs against our purely conventional forces, and they almost certainly know it. The only hard part is demonstrating our will to do so.

The bigger problem is the prospect of one of the Great Powers themselves doing the math in time of crisis and coming to the conclusion that having a world-class conventional military, plus a civil nuclear power industry capable of cobbling together a hundred or more H-bombs on short notice, minus anyone else having any nuclear deterrent at all, equals a fundamental game change.

And the two threats aren’t entirely decoupled. The most likely crisis I can see for great-power renuclearization would be the United States, as Officially Designated World Policeman, having to take down a rogue states by sending the 82nd airborne into the cross-hairs of someone else’s illicit nuclear missiles. That happens, and particularly if it happenes more than once, it’s going to be very tempting for Americans watching lead-lined caskets coming home to decide that Global Zero isn’t working, but Pax Nuclear Americana just might…

I honestly don’t see a stable path to an enduring Global Zero, and I think you’d need a remarkably trouble-free world to want to risk a generation or two of existential instability during the transition. But something on the order of a hundred warheads per UNSC permanent member, that’s probably enough to deter even a would-be rogue superpower.

“can take down a classic rogue state even if we spot them a dozen A-bombs”

– presumably by “take down” you mean that the great power would suffer ~ 10 million casualties from those bombs that get through?

Rationalist –

Fundamentally I have two concerns.

One, that the odds of nuclear weapons use (particularly against civilian or mixed target areas) be minimized for the near, mid, and long terms.

Two, that we as a world and the US in particular not face a situation where some genocidal maniac runs rampant on any scale again a la Hitler. Though I doubt it sincerely it helps to consider a US maniac leader (other countries take the argument better if we avoid special pleading).

There are three nuclear policy strategies and a lot more geopolitics at play. In short, all of disarmament, global zero, and nonproliferation are in play in our domain.

Five thousand or so words I am not going to type tonight on my iPhone later, to summarize in short, geopolitical uncertainty is a huge risk. Disarmament, i.e. reductions up to an order of magnitude less, seem stabilizing to me under just about any scenario. Nonproliferation seems stabilizing. The arguments that zero is ultimately stable or that paths to it are ultimately stable fall somewhat short of convincing.

Geopolitical developments one can hope for but not predict change the fifty-plus year game. My hope is that it becomes a moot point by then. But I think prematurely focusing on zero increases bad actors incentive to cheat and ultimately increases the risks of genocide or nuclear weapons use, which are my core goals.

So the consensus here seems to be that global zero makes it way too tempting for someone to cheat and be the world’s only nuclear power.

Since this point is not exactly subtle, why have so many high-profile people got behind global zero? Is it just a way for them to signal how “nice” they are to those ordinary people who don’t know better? I. E. Is global zero just a PR trick for it’s backers? Or is there some compelling counterargument?

Thanks for the responses, guys.

Rationalist: w/re “~10 million casualties”, I think you greatly overestimate the threat posed by small, simple nuclear arsenals; the historic record is ~100,000 dead per fission weapon deployed against an essentially undefended target, and the United States would be anything but defenseless in taking on a future rogue state.

As far as motivations behind Quixotic quests for Global Zero; part of that I think is discomfort with the alternatives. Deterrence, even in a world of effective arms control and nonproliferation, can never be 100.00% effective, so accepting the continued existence of nuclear weapons means accepting the ongoing small probability (which translates to long-term certainty) that some of them will be used.

That’s not the worst possible outcome, but if the idea of even a limited nuclear exchange seems sufficiently revolting as to merit a negative-infinity score in one’s ethical calculus, one will be highly motivated to find solutions which have zero nuclear weapons and thus zero probability of nuclear war. Which is illusory, as even Global Zero leads to a small ongoing probability of nuclear war, but it is an understandable and appealing illusion.

So no, I don’t think the backers of Global Zero are just posturing, not most of them anyhow. Wrong, in the sense of excessively optimistic, but sincere.

@John Schilling:

The silly thing about the “long run” argument is that in the long run (60+ years) other threats will almost certainly become more serious than nuclear war. Advanced bioweapons, synthetic biology, nanotechnological threats and eventually advanced AI threats will come to dominate.

Also yes, a few fission weapons wouldn’t be as bad as I was making out. I had a bit of a brain fart and forgot that getting H-bombs is significantly harder, and unlikely to be a rogue state’s first port of call.

I don’t think the argument about whether or not Zero is feasible needs to be settled today. We have a lot of hard work ahead of us in getting to much lower numbers first – if and when we get to the ~100 level we can finish nutting out the issue of Zero. I’m sure the view from there will be much clearer, too.

Addressing the concepts in the post, mostly in the sequence they were presented:

Big Brother and the Holding Co. were alright as a dance band. The musical experimentation was difficult. Often, the best innovations took place when passages attempted to be organized and very standard blues. However, that was a long time ago.

Janis was a different story. As with your video-linked group, In the very earliest year to year-and-a-half, it seemed that Janis, too, ‘came along’, veritably burst upon the ‘scene’. With raw talent and intensity, for sure. Regrettably, Janis got a physical vocal cord problem very early in her career. A voice that sang blues like Baez sang folk, very quickly became something else. Still with drive, raw, and the lady was strong.

To the negotiation topic. What occurs to me, including taking the helpful commenters’ observations into consideration, is that there is a multiplicity of forces affecting how negotiations are shaped.

Presidencies have their own aura. Wars have aftermath. Technologies grow apace. In sum, there are dynamic intersections of multiple factors, and the best negotiators recognize opportunities to achieve stabilizing aims.

Reviewing the interesting series of Kristensen articles, I would have preferred a time graph extent farther back than 1977 ending with the Carter administration, instead going all the way to first use in the Truman era which began in 1945.

The concept of war shifted thru several paradigms in the longer timespan, as did the principal countries’ views of the place of nuclear arms, chemical, biological, space, guided missles, drones, submarines, silos; and there were new theories of guerrilla warfare, as well as old configurations of personal terrorism.

I have a difficult time ascribing negotiator-success preponderantly to US Republican presidents, viewing all these factors.

John:

Many thanks for weighing in. I asked Hans to begin the graphic with the Carter administration, mostly because the stockpile lines were seriously vertical from Truman onwards.

Treaty making usually presumes treaty ratification. If the Washington-based Republican Party sees little value in treaties, Democratic administrations are obliged to reduce deployed nuclear forces by alternative means. Treaty alternatives also require Congressional approval, but not to standards that reward obstructionists.

As for Big Brother and the Holding Company, you saw musicality that eluded me. Maybe you saw them live. The albums were frustrating: Janis Joplin deserved way better. I felt the same way with Rosanne Cash’s “Seven Year Itch.” I’m a peaceable man, but whenever I hear that astounding track, I want to forcibly seize the drummer.

MK

Ouch. Make that Seven Year Ache.

The issue I took with Carter was the already mentioned above partisan stereotyping. We heard a reprise at last week’s convention, I believe; one-term, and all that.

The cold war was many things, though; and I admired Carter’s efforts.

The Big Brother and the Holding Co. mention in my comment intended to depict just that, their danceability. Live improvisation was a forte, but studio musicianship showed the seams. Even some live recordings revealed the orchestra arrangement barriers the guys were addressing. A difficult time. And Janis was meteoric, especially in person and very early giving voice to Big Brother but mostly enunciating her own dreams.

Regarding “Global Zero”:

Have any of you ever attempted balancing an egg on its end atop a table? It is possible, theoretically. But unless the egg is abnormally flat, the best you will ever get is an unstable equilibrium where the slightest jostling will cause it to become unbalanced. The egg will fall until its center of balance is as low as possible. While sitting on its oblong (but still curved) side, the egg is not really stable. But is not likely to roll too far or too fast to prevent it from rolling off the table – as long as someone is paying attention.

While we have few data points on nuclear buildup, we have only one on the state of near-“Global Zero.” It was unstable. The U.S. and U.S.S.R. only reached stability after four decades of buildup. How much more difficult would it be with multiple nuclear powers, including potential states that currently do not have the capability? The balancing-egg problem can be reduced to a two-dimensional problem. Extending the analogy to the Cold War and the reach toward “Global Zero” would be like balancing a ten-dimensional egg. If you’ve taken a physics, engineering, or math course that covers statics and dynamics, you know how much complexity is introduced in increasing the dimensionality of the problem.

Another math-related analogy: the graph looks largely like a stepwise function, but it would be interesting to see a multi-variable analysis of the line to see whether it goes to zero or approaches a non-zero asymptote.

In my view, zero is the right objective, for reasons I’ve written about in these posts. We will reduce only as far and as fast as political and security conditions permit.

This won’t be a mechanistic, apolitical process, i.e., we get to zero in stages by certain dates and with certain numbers. Put another way, the more ambitious the plan, the less certainty accompanies it.

It’s easy to crticize zero by applying today’s political conditions and security concerns against this number. We won’t get anaywhere close to zero with contemporary conditions; we might get to 1,000 deployed warheads on strategic nuclear delivery vehicles.

MK

@rationalist (and for all):

It would be good to understand the basics concepts behind explosions:

Bigger bombs (of any type…convention, or otherwise)are not efficient.

1. for any radiation output (IR, visible light, any EM radiation), any source’s EM energy decreases with distance according to the Inverse Square Law:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inverse-square_law

2. Blast overpressure (again, applies to all explosions, conventional or otherwise) follow a different scaling factor, where the blast effect decreases even more dramatically with distance:

http://www.questconsult.com/99-spring.pdf

In short, bigger bombs run afoul of exponential diminishing returns on effect.

That, along with the huge expense and waste of material in building and delivering big bombs (of any kind, conventional or otherwise) has resulted in the idea of using the minimum explosive power possible, according to the high accuracy and precision of the delivery to the detonation point.

It is called ‘economy of force’, and has been a basic military principle for a long time…technology has now enabled it in spades.

This is why, combined with the much lower political ramifications, that conventional munitions rule the day.

It’s not “exponential diminishing” returns.

Inverse square and inverse cube are both polynomial.

I think the meaning of the term “exponentially” just completely died. It’s been on it’s last legs for a while now… but being used to describe a situation which is explicitly polynomial finally killed it.

Anyway just because the returns are diminished for big explosions doesn’t mean a nuke is less militarily useful than the equivalent cost worth of grenades or bombs. Nukes also have a factor of about 10^8 better energy density. Which means that 1 ton of nuke is still more destructive than one ton of small bombs.